Call it Downsview’s greatest gift to the world of aviation.

Many successful aircraft were developed at de Havilland’s Downsview plant over the course of its fifty-year run - the Mosquito, the Tiger Moth, the Chipmunk, the Buffalo, the Twin Otter to name but a few – but arguably none had the magnitude of impact of the DHC-2 Beaver.

The Royal Canadian Mint honoured the de Havilland Beaver twice, by placing its image on coins in 1999 and 2008. And it was named one of the top ten Canadian engineering accomplishments of the twentieth century by the Canadian Engineering Centennial Board.

Like all aircraft companies at the end of the Second World War, de Havilland was looking for a way to transition from wartime to peacetime production. At the top of the company’s priority list was developing a new Canadian bush plane. The fact that the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests had already shown interest in purchasing 25 planes suitable for use in the rugged terrain of northern Ontario was just the incentive the company needed.

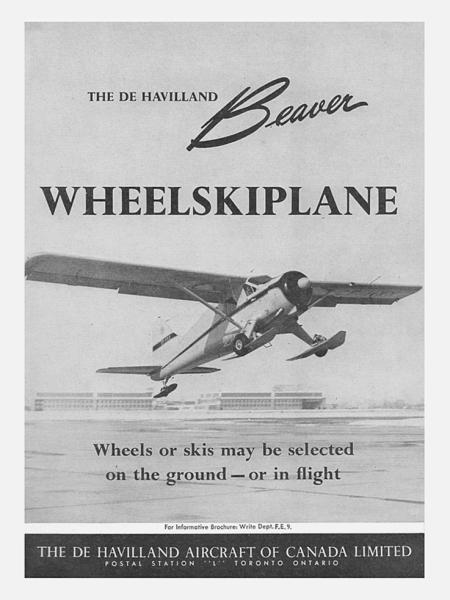

In January 1947, de Havilland hired legendary pilot C.H. “Punch” Dickins, who’d been flying the Canadian bush since 1928, to lead the project. Dickins surveyed dozens of his fellow bush pilots to ascertain what they wanted in the new plane. “Lots of power” was the reply. They were also looking for a plane that could take off and land in tight spaces, was as rugged as the territory it was designed to serve, had plenty of room for cargo, and could be easily adapted for wheels, skis, and floats.

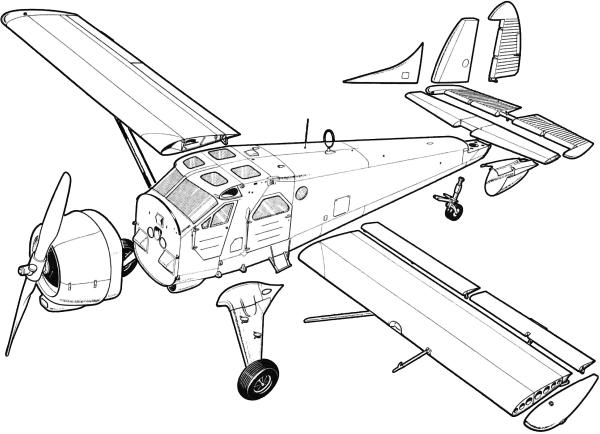

The de Havilland engineers went to work. They chose the 450 horsepower Pratt and Whitney Wasp Jr. engine to meet the power needs. To achieve a short takeoff and landing, they added extra length to the wings and mounted them on the plane’s shoulders. They widened the doors to ease loading and unloading. The plane could carry five passengers plus the pilot, and all but the pilot’s seat could be removed for extra cargo room. The fuel was stored in easy-to-reach tanks under the floor. And to add toughness, for the first time, the entire plane was made of metal.

When it came to giving the plane a name, there was only one possible option. This hard-working plane would be named after the hardest working animal in the Canadian north – the beaver.

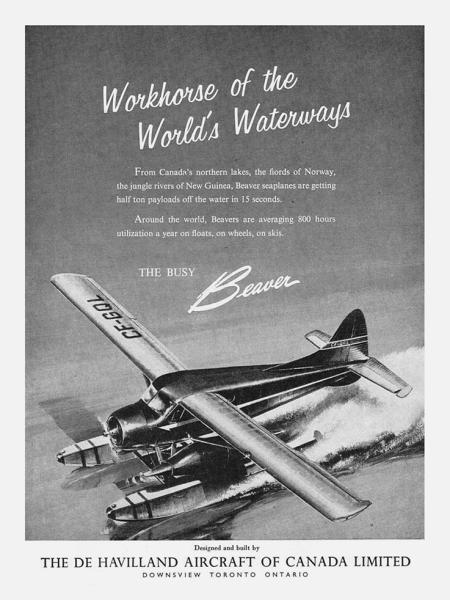

Soon, they were everywhere. The Beaver played a critical role in opening up the Canadian north to tourism and resource extraction. And they were not confined to Canada. A Globe and Mail article in 1953 declared that the Beaver was “a familiar sight on all six continents, in more than 20 nations and dependencies, on war fronts, at holiday resorts, in the tropics and over both frigid poles.”

The Beaver was one of the most commercially successful planes de Havilland ever produced, largely due to its popularity in the United States. In 1951, de Havilland entered the Beaver in a competition organized by the U.S. military to find a replacement for the Army’s aging fleet of Cessnas. Against tough American competition, and some Congressional opposition, the Canadian plane emerged victorious. Of the almost 1,700 Beavers produced between 1947 and 1967, nearly a thousand were purchased by the U.S. military, making it by far the plane’s largest single buyer. The plane saw service in Korea and Vietnam, primarily doing rescue operations, cargo and passenger transport, and aerial photography.

Today, more than half a century since the last Beaver rolled out of the Downsview assembly plant, it remains one of the most beloved aircraft ever produced. Hundreds of them are still in service. The Beaver is still sought after by charter companies to deliver critical supplies or fly people into remote corners of the world to fish, hunt or view wildlife. Some are owned by private collectors, like Star Wars actor Harrison Ford. Many more can be found in aviation museums.

And in perhaps the greatest testament to the Beaver’s enduring appeal, a plane that cost about twenty thousand dollars to buy new in the late 1940s, today costs up to half a million.

More Stories

Downsview’s Queer Histories & The LGBT Purge

From the Two-Spirit Pow-Wows in Downsview Park, to the queer-positive roller derbies in the Downsview Supply Depot, to inclusion at Downsview United Church, today, 2SLGBTQI+ people are at home on the Downsview lands.

Gore Vaughn Plank Road

Getting goods to market was a constant challenge for Downsview farmers in the years before Confederation. Roads were unpaved and their carts and wagons would get bogged down in the muck when it rained or during the spring thaw.